Edinburgh Scotland

The Railway Route (Red) from London to Edinburgh Scotland

This is the picture I took in 1983 of the Scott Memorial.

The Scott Monument is a Victorian Gothic monument to Scottish author Sir Walter Scott. It is the largest monument to a writer in the world.[1] It stands in Princes Street Gardens in Edinburgh, opposite the Jenners department store on Princes Street and near to Edinburgh Waverley Railway Station, which is named after Scott's Waverley novels.

Design and concept

The tower is 200 feet 6 inches (61.11 m) high, and has a series of viewing platforms reached by a series of narrow spiral staircases giving panoramic views of central Edinburgh and its surroundings. The highest platform is reached by a total of 288 steps. It is built from Binny sandstone quarried near Ecclesmachan in West Lothian.In terms of its location, it is placed on axis with South St David Street, the main street leading off St Andrew Square to Princes Street, and is a focal point within that vista, its scale being large enough to totally screen the Old Town behind. As seen from the south side, Princes Street Gardens, its location appears more random, but it totally dominates the Eastern section of the gardens, through a combination of its scale and elevated position relative to the sunken gardens.

I took this picture. Beautiful clock made of flowers. It appears to be a university clock.

History

Scott's Monument as it appeared when nearly finished, in October 1844.

Masons working on the Monument, photographed by Hill & Adamson in the early 1840s

The Sir Walter Scott statue designed by John Steell, located inside the Scott Monument

John Steell was commissioned to design a monumental statue of Scott to rest in the space between the tower's four columns. Steell's statue, made from white Carrara marble, shows Scott seated, resting from writing one of his works with a quill pen and his dog Maida by his side. The monument carries 64 figures (carried out in three phases) of characters from Scott's novels by a variety of Scots sculptors including, Alexander Handyside Ritchie, John Rhind, William Birnie Rhind, William Brodie, William Grant Stevenson, David Watson Stevenson, John Hutchison, George Anderson Lawson, Thomas Stuart Burnett, William Shirreffs, Andrew Currie, George Clark Stanton, Peter Slater,[2] and two female representatives, Amelia Robertson Hill (who also made the statue of David Livingstone immediately east of the monument), who contributed three figures to the monument,[3] and the otherwise unknown Katherine Anne Fraser Tytler.

The foundation stone was laid on 15 August 1840. Following permission by an Act of Parliament (the Monument to Sir Walter Scott Act 1841 (4 & 5 Vict.) C A P. XV.), construction began in 1841 and ran for nearly four years. The tower was completed in the autumn of 1844, with Kemp's son placing the finial in August of the year. The total cost was just over £16,154.[4] When the monument was inaugurated on 15 August 1846, George Meikle Kemp himself was absent, having fallen into the Union Canal while walking home from the site on the foggy evening of 6 March 1844 and drowned.

Statues and locations

In total (excluding Scott and his dog), there are 68 figurative statues on the monument of which 64 are visible from the ground. Four figures are placed above the final viewing gallery and are only visible by telephoto or (at a very distorted angle) from the viewing gallery itself. In addition, eight kneeling Druid figures support the final viewing gallery. There are 32 unfilled niches at higher level.Sixteen heads of Scottish poets and writers appear on the lower faces, at the top of the lower pilasters. The heads (anti-clockwise from the NW) represent: James Hogg; Robert Burns; Robert Fergusson; Allan Ramsay; George Buchanan; Sir David Lindsay; Robert Tannahill; Lord Byron; Tobias Smollett; James Beattie; James Thomson; John Home; Mary, Queen of Scots; King James I of Scotland; King James V of Scotland; and William Drummond of Hawthornden.

In total, 93 persons are depicted, plus two dogs and a pig.

Edinburgh - New Town (taken from Edinburgh Castle

New Town - Edinburgh

Wikipedia

The New Town is a central area of Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. It is often considered to be a masterpiece of city planning and, together with the Old Town, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1995. It was built in stages between 1767 and around 1850, and retains much of the original neo-classical and Georgian period architecture. Its most famous street is Princes Street, facing Edinburgh Castle and the Old Town across the geographical depression of the former Nor Loch.

Preparing the ground

The idea of a New Town was first suggested in the late 17th century when the Duke of Albany and York (later King James VII and II), when resident Royal Commissioner at Holyrood, encouraged the idea of having an extended regality to the north of the city and a North Bridge. He gave the city a grant:That, when they should have occasion to enlarge their city by purchasing ground without the town, or to build bridges or arches for the accomplishing of the same, not only were the proprietors of such lands obliged to part with the same on reasonable terms, but when in possession thereof, they are to be erected into a regality in favour of the citizens.It is possible that, with such patronage, the New Town may have been built many years earlier than it was but, in 1682, the Duke left the city and became King in 1685, only to lose the throne in 1688.[1]

The decision to construct a New Town was taken by the city fathers, after overcrowding inside the Old Town city walls reached breaking point and to prevent an exodus of wealthy citizens from the city to London.[2] The Age of Enlightenment had arrived in Edinburgh, and the outdated city fabric did not suit the professional and merchant classes who lived there. Lord Provost George Drummond succeeded in extending the boundary of the Royal Burgh to encompass the fields to the north of the Nor Loch, the heavily polluted body of water which occupied the valley immediately north of the city. A scheme to drain the Loch was put into action, although the process was not fully completed until 1817. Crossing points were built to access the new land; the North Bridge in 1772, and the Earthen Mound, which began as a tip for material excavated during construction of the New Town. The Mound, as it is known today, reached its present proportions in the 1830s.

As the successive stages of the New Town were developed, the rich moved northwards from cramped tenements in narrow closes into grand Georgian homes on wide roads. However, the poor remained in the Old Town.

The First New Town

Plan for the New Town by James Craig (1768)

Craig's original plan has not survived but it has been suggested that it is indicated on a map published by John Laurie in 1766.[3] This map shows a diagonal layout with a central square reflecting a new era of civic Hanoverian British patriotism by echoing the design of the Union Flag. Both Princes Street and Queen Street are shown as double sided. A simpler revised design reflected the same spirit in the names of its streets and civic spaces.[2]

Street names

View of the New Town from Edinburgh Castle, largely obscured by modern shopping developments

King George rejected the name St. Giles Street, St Giles being the patron saint of lepers and also the name of a slum area or 'rookery' on the edge of the City of London. It was therefore renamed Princes Street after his sons. The name of St. George's Square was changed to Charlotte Square, after the Queen, to avoid confusion with the existing George Square on the South Side of the Old Town. The westernmost blocks of Thistle Street were renamed Hill Street and Young Street, making Thistle Street half the length of Rose Street. The three streets completing the grid, Castle, Frederick and Hanover Streets, were named for the view of the castle, King George's father Frederick, and the name of the royal family respectively.

Development

Craig's proposals hit further problems when development began. Initially the exposed new site was unpopular, leading to a £20 premium being offered to the first builder on site. This was received by John Young who built Thistle Court, the first buildings in the New Town, at the east end of Thistle Street in 1767. Instead of building as a terrace as envisaged, he built a small courtyard.[4] Doubts were overcome soon enough, and further construction started in the east with St. Andrew Square.Craig had proposed that George Street be terminated by two large churches, situated within each square. Sir Lawrence Dundas, the landowner, decided to build his own home here, and commissioned a design from Sir William Chambers. The resulting Palladian mansion, completed in 1774, is now the headquarters of the Royal Bank of Scotland. St. Andrew's Church had to be built on a site on George Street. The lack of a visual termination at the end of this street was remedied in 1823 with William Burn's monument to Henry Dundas.

The first New Town was completed in 1820, with the completion of Charlotte Square. This was built to a design by Robert Adam, and was the only architecturally unified section of the New Town. Adam also produced a design for St. George's Church, although his design was superseded by that of Robert Reid. The building, now known as West Register House, now houses part of the National Archives of Scotland. The North side of Charlotte Square features Bute House—formerly the official residence of the Secretary of State for Scotland. Since the introduction of devolution in Scotland, Bute House is the official residence of the First Minister of Scotland.

Montage image of Robert Adam's north side of Charlotte Square. Bute House, official residence of the First Minister of Scotland, is in the centre.

Redevelopment

Surviving Georgian buildings in Princes Street

It did not take long for the commercial potential of the site to be realised. Shops were soon opened on Princes Street, and during the 19th century the majority of the townhouses on that street were replaced with larger commercial buildings. Occasional piecemeal redevelopment continues to this day, though most of Queen Street and Thistle Street, and large sections of George Street, Hanover, Frederick and Castle Streets, are still lined with their original late 18th century buildings. Very large sections of the Second New Town, built from the early 19th century are also still exactly as built.

Later additions

Great King Street. Part of the northern extension to the original New Town

Moray Place. Part of the western extension to the original New Town

Regent Terrace. Part of the eastern extension of the original New Town

Drumsheugh Gardens. Part of the further western, Victorian extension to the New Town

In order to extend the New Town eastwards, the Lord Provost, Sir John Marjoribanks, succeeded in getting the elegant Regent Bridge built.[6] It was completed in 1819. The bridge spanned a deep ravine with narrow inconvenient streets and made access to Calton Hill much easier and agreeable from Princes Street.[7] Edinburgh Town Council organised a competition for plans to develop the Eastern New Town but the result was inconclusive. Eventually designs by the architect William Henry Playfair were used to develop Calton Hill and Edinburgh’s Eastern New Town from 1820 onwards.[8] Playfair’s designs were intended to create a New Town even more magnificent than Craig's.[9] Regent Terrace, Calton Terrace and Royal Terrace were built but the developments to the north of London Road were never fully completed. On the south side of Calton Hill various monuments were erected as well as the Royal High School in Greek revival style.

A few modest developments in Canonmills were started in the 1820s but none were completed at that time. For several decades the operations of the tannery at Silvermills inhibited development in the immediate vicinity. From the 1830s onward, development slowed but following the completion in 1831 of Thomas Telford’s Dean Bridge, the Dean Estate had some developments built. These included the Dean Orphanage (now the Dean Gallery), Daniel Stewart's College, streets to the Northeast of Queensferry Street (in the 1850s), Buckingham Terrace (in 1860) and Learmonth Terrace (in 1873).[5]

In the 19th century Edinburgh's second railway, the Edinburgh, Leith and Newhaven Railway, built a tunnel under the New Town to link Scotland Street with Canal Street (later absorbed into Waverley Station). After its closure, the tunnel was used to grow mushrooms, and during World War 2 as an air raid shelter.

Principal Losses

Given the great continuity of the built form in the New Town it is quicker to list what little has gone, rather than muse on the numerous streets which are unchanged.Bellevue House by Robert Adam, which became the Excise or Custom House, was built in 1775, before the New Town reached the area, in what is now Drummond Place Gardens. Great King Street and London Street in the Northern or Second New Town were aligned on this building but it was demolished in the 1840s due to the construction of the Scotland Street railway tunnel below.[10]

Lost streets include those in the St James Square area, demolished in the 1960s to make way for the St James Shopping Centre and offices for the Scottish Office. This mainly tenemental area, reported as having a population of 3,763, was demolished largely on the basis of being slums with only 61 of 1,100 dwellings being considered fit for habitation.

Also demolished as slums was most of Jamaica Street at the west end of the Second New Town.

Culture

New Town street lamps

The Cockburn Association (Edinburgh Civic Trust) is prominent in campaigning to preserve the architectural integrity of the New Town.

Shopping

The New Town contains Edinburgh's main shopping streets. Princes Street is home to many chain shops, as well as Jenners department store, an Edinburgh institution. George Street, once the financial centre, now has numerous modern bars, many occupying former banking halls, while Multrees Walk on St. Andrew Square is home to Harvey Nichols and other designer shops. The St. James Centre, at the east end of the New Town, is an indoor mall completed in 1970. Often considered an unwelcome addition to New Town architecture, it includes a large branch of John Lewis. Also, by the Waverley Railway Station lies the Princes Mall, which contains many high street stores.*******************************

Edinburgh - Old Town

Old Town Edinburgh

Wikipedia

The Old Town (Scots: Auld Toun) is the name popularly given to the oldest part of Scotland's capital city of Edinburgh. The area has preserved much of its medieval street plan and many Reformation-era buildings. Together with the 18th-century New Town, it forms part of a protected UNESCO World Heritage Site.[

Royal Mile

The "Royal Mile" is a name coined in the early 20th century for the main artery of the Old Town which runs on a downwards slope from Edinburgh Castle to both Holyrood Palace and the ruined Holyrood Abbey. Narrow closes (alleyways), often no more than a few feet wide, lead steeply downhill to both north and south of the main spine which runs west to east.Notable buildings in the Old Town include St. Giles' Cathedral, the General Assembly Hall of the Church of Scotland, the National Museum of Scotland, the Old College of the University of Edinburgh and the Scottish Parliament Building. The area has a number of underground vaults and hidden passages that are relics of previous phases of construction.

No part of the street is officially called The Royal Mile in terms of legal addresses. The actual street names (running west to east) are Castlehill, Lawnmarket, High Street, Canongate and Abbey Strand.[2]

Street layout

The street layout, typical of the old quarters of many northern European cities, is made especially picturesque in Edinburgh, where the castle perches on top of a rocky crag, the remnants of an extinct volcano, and the main street runs down the crest of a ridge from it. This "crag and tail" landform was created during the last ice age when receding glaciers scoured across the land pushing soft soil aside but being split by harder crags of volcanic rock. The hilltop crag was the earliest part of the city to develop, becoming fortified and eventually developing into the current Edinburgh Castle. The rest of the city grew slowly down the tail of land from the Castle Rock. This was an easily defended spot with marshland on the south and a man-made loch, the Nor Loch, on the north. Access up the main road to the settlement was therefore restricted by means of various gates and the city walls, of which only fragmentary sections remain.The original strong linear spine of the Royal Mile only had narrow closes and wynds leading off its sides. These began to be supplemented from the late 18th century with wide new north–south routes, beginning with the North Bridge/South Bridge route, and then George IV Bridge. These rectilinear forms were complemented from the mid-19th century with more serpentine forms, starting with Cockburn Street, laid out by Peddie and Kinnear in 1856, which specifically improved access between the Royal Mile and the newly rebuilt Waverley Station.

The Edinburgh City Improvement Act of 1866 further added to the north south routes. This was devised by the architects David Cousin and John Lessels.[3] It had quite radical effects:

- St Mary's Wynd was demolished and replaced by the much wider St Mary's Street with all new buildings.

- Leith Wynd which descended from the High Street to the Low Calton was demolished. Jeffrey Street started from Leith Wynd's junction with the High Street, opposite St Mary's Street, but bent west to join Market Street.

- East Market Street was built to connect Market Street and New Street.

- Blackfriars Street was created by the widening of Blackfriars Wynd, removing all the buildings on the east side.

- Chambers Street was created, replacing N College Street and removing Brown Square (west) and Adam Square (east). It was named after the then Lord Provost of Edinburgh, Sir William Chambers, and his statue placed at its centre.

- Guthrie Street was created, linking the new Chambers Street to the Cowgate.

Sections

In addition to the Royal Mile, the Old Town may be divided into various areas, namely from west to east:- West Port, the old route out of Edinburgh to the west

- Grassmarket, the area to the south-west

- Edinburgh Castle

- The Cowgate, the lower southern section of the town [4]

- Canongate, a name correctly applied to the whole eastern district

- Holyrood, the area containing Holyrood Palace and Holyrood Abbey

- Croft-An-Righ, a group of buildings north-east of Holyrood

Residential buildings

Buildings in the High Street

Traditionally buildings were less dense in the eastern, Canongate, section. This area underwent major slum clearance and reconstruction in the 1950s, thereafter becoming an area largely of Council housing. Further Council housing was built on the southern fringe of the Canongate in the 1960s and 1970s in an area generally called Dumbiedykes. From 1990 to 2010 major new housing schemes appeared throughout the Canongate. These were built to a much higher scale than the traditional buildings and have greatly increased the population of the area.

Major events

A replica gas lamp in the Old Town

During the Edinburgh Festival the High Street and Hunter Square become gathering points where performers "on the Fringe" advertise their shows, often through street performances.

On 7 December 2002, a large fire destroyed a small but dense group of old buildings on the Cowgate and South Bridge. It destroyed the famous comedy club, The Gilded Balloon, and much of the Informatics Department of the University of Edinburgh, including the comprehensive artificial intelligence library.[5] The site was redeveloped 2013-2014 with a single new building, largely in hotel use.

Old Town Renewal Trust

In the 1990s the Old Town Renewal Trust in conjunction with the City of Edinburgh developed an action plan for renewal [6][7][8][9]Proposed Development

the Jeffrey Street arches which are due to be redeveloped in 2015

******************************

Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Scotland

Edinburgh and culture

Edinburgh

Edinburgh-view-from-castleEdinburgh is the capital of Scotland and it is located in central eastern Scotland, near the Firth of Forth, close to the North Sea. Thanks to its spectacular rocks, rustic buildings and a huge collection of medieval and classic architecture, including numerous stone decorations, it is often considered one of the most lively cities in Europe. Scottish people called it Auld Reekie, Edina, Athens of the North and Britain’s Other Eye.

Edinburgh is not only one of the most beautiful cities in Europe, it is a city with a fantastic position. The view falls on all sides – green hills, the hint of the blue sea, the silhouettes of the buildings and the red cliffs. It is a city that calls you to explore it by foot – narrow streets, passageways, stairs and hidden church yards on every step will pull you away from the main streets.

edinburghThe city is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the UK. It is the capital of Scotland and home to many tourist attractions. A visit here will be well worth it, considering the numerous things you can do and see. Most of the structures in the Old Town have remained in their original form over the years. Charming medieval relics are plenty in this section of the city. In contrast, orderly Georgian terraces line the streets of the New Town. The general urban scenery is a blend of ancient structures and modern architecture, which gives the city a unique character. In 1995, the Old Town was listed as a UNESCO Heritage Site. With year round festivals, a throbbing nightlife and an entertaining arts scene, Edinburgh never falls short of interesting travel ventures for tourists.

Edinburgh-scott-monumentEdinburgh is a city of literature – it was the first city to be called the UNESCO city of Literature. Visit the National Library of Scotland, the Museum of Writers, the Scottish Center of Story Telling, the Library of Poetry and many other libraries. The list of famous Scottish authors is very long, just choose your favorite one and enjoy researching everything linked to that person: Arthur Conan Doyle, J.K. Rowling, Robert Fergusson, Robert Burns, Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson, Allan Ramsay, Alexander McCall Smith, Ian Rankin, Liz Lochhead, James Kelman, Alasdair Grey, Dorothy Dunnett, Muriel Spark, Lewis Grassic Gibbon, Neil M. Gunn, John Buchan, Hugh MacDiarmid…

Edinburgh is a beautiful city filled with stunning geology. Its diverse landscape is worth seeing, as it transforms from the volcanic Pentland Hills in the south, to the seaside resort of Portobello in the East. To get a birds-eye view of the city, you can scale Arthur’s Seat, an extinct volcano, which is one of the most popular attractions.

Edinburgh Castle

No matter how you get to Edinburgh – by train, bus or cab from the airport – Edinburgh Castle is a must see destination. You don’t need to be a good strategist to know why the castle is located at that spot – the volcanic hill with the sharp cliffs that have been cut by glaciers is the main reason Edinburgh is located here. From this spot it is very easy to defend Edinburgh from an attack from all directions.

Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle has changed its owners many times; it was captured by the English and Scottish,. When you arrive you must, visit St. Margaret’s chapel – the oldest part in the castles complex and it is likely the oldest building that can be found in Edinburgh; it was built presumably around 1130. in the honour of queen Margaret who lived in the 11th century, and also boasts two beautiful rustic chandeliers that date respectively from 1695 and 1735. Edinburgh Castle is one of the attractions that you simply must see. It is the most visited tourist attraction in Scotland.

Map of Edinburgh

Edinburgh Festival

The Edinburgh international festival is more than a festival. It is an international festival, that offers you various artist performances (classical music, opera, ballet, drama). The Summer Edinburgh Festival traditionally is held during three weeks in August every year, and Edinburgh attract visitors from all around the world. You can also plan a visit during the Fringe Festival, where you will see comedy performances, drama and artists. You can also can visit the Book Festival, Jazz Festival and TV Festival, as well as others. Yes, Scottish folks love a good festival!

The Gate

I took these pictures, Lots of grays and browns and dark greens. Very Scottish.....

I took this foreboding picture. It looks dark and stormy and gloomy...oh my! I love it! :)

Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle from Calton Hill

I like this view of the City

Another view of Edinburgh Castle

Charlotte resting in front of the castle

Charlotte testing a well deserved rest.

The Castle from Calton Hill.

The Royal Palace at Edinburgh Castle.

Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle on the Mountain

Edinburgh Castle is a historic fortress which dominates the skyline of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, from its position on the Castle Rock. Archaeologists have established human occupation of the rock since at least the Iron Age (2nd century AD), although the nature of the early settlement is unclear. There has been a royal castle on the rock since at least the reign of David I in the 12th century, and the site continued to be a royal residence until 1633. From the 15th century the castle's residential role declined, and by the 17th century it was principally used as military barracks with a large garrison. Its importance as a part of Scotland's national heritage was recognised increasingly from the early 19th century onwards, and various restoration programmes have been carried out over the past century and a half. As one of the most important strongholds in the Kingdom of Scotland, Edinburgh Castle was involved in many historical conflicts from the Wars of Scottish Independence in the 14th century to the Jacobite Rising of 1745. Research undertaken in 2014 identified 26 sieges in its 1100-year-old history, giving it a claim to having been "the most besieged place in Great Britain and one of the most attacked in the world".[3]

Few of the present buildings pre-date the Lang Siege of the 16th century, when the medieval defences were largely destroyed by artillery bombardment. The most notable exceptions are St Margaret's Chapel from the early 12th century, which is regarded as the oldest building in Edinburgh,[4] the Royal Palace and the early-16th-century Great Hall, although the interiors have been much altered from the mid-Victorian period onwards. The castle also houses the Scottish regalia, known as the Honours of Scotland and is the site of the Scottish National War Memorial and the National War Museum of Scotland. The British Army is still responsible for some parts of the castle, although its presence is now largely ceremonial and administrative. Some of the castle buildings house regimental museums which contribute to its presentation as a tourist attraction.

The castle, in the care of Historic Scotland, is Scotland's most-visited paid tourist attraction, with over 1.4 million visitors in 2013.[5] As the backdrop to the Edinburgh Military Tattoo during the annual Edinburgh International Festival the castle has become a recognisable symbol of Edinburgh and of Scotland and indeed, it is Edinburgh's most frequently visited visitor attraction—according to the Edinburgh Visitor Survey, more than 70% of leisure visitors to Edinburgh visited the castle.

History

Pre-history of the Castle Rock

Geology

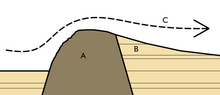

Diagram of a crag and tail feature, such as the Castle Rock: A is the crag formed from the volcanic plug, B is the tail of softer rock, and C shows the direction of ice movement. In the case of Edinburgh, the castle stands on the crag (A) with the Royal Mile extending along the tail (B)

The summit of the Castle Rock is 130 metres (430 ft) above sea level, with rocky cliffs to the south, west and north, rising to a height of 80 metres (260 ft) above the surrounding landscape.[7] This means that the only readily accessible route to the castle lies to the east, where the ridge slopes more gently. The defensive advantage of such a site is self-evident, but the geology of the rock also presents difficulties, since basalt is extremely impermeable. Providing water to the Upper Ward of the castle was problematic, and despite the sinking of a 28-metre (92 ft) deep well, the water supply often ran out during drought or siege,[8] for example during the Lang Siege in 1573.[9]

Earliest habitation

The castle is built on a volcanic rock, as seen here from the West Port area

The Castle seen from the North

The archaeological evidence is more reliable in respect of the Iron Age. Traditionally, it had been supposed that the tribes of central Scotland had made little or no use of the Castle Rock. Excavations at nearby Dunsapie Hill, Duddingston, Inveresk and Traprain Law had revealed relatively large settlements and it was supposed that these sites had been chosen in preference to the Castle Rock. However, the excavation in the 1990s pointed to the probable existence of an enclosed hill fort on the rock, although only the fringes of the site were excavated. House fragments revealed were similar to Iron Age dwellings previously found in Northumbria.[27]

The 1990s dig revealed clear signs of habitation from the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, consistent with Ptolemy's reference to "Alauna". Signs of occupation included some Roman material, including pottery, bronzes and brooches, implying a possible trading relationship between the Votadini and the Romans beginning with Agricola's northern campaign in AD 82, and continuing through to the establishment of the Antonine Wall around AD 140. The nature of the settlement in this period is inconclusive, but Driscoll and Yeoman suggest it may have been a broch, similar to the one at Edin's Hall near Duns in the Scottish Borders.[28]

Early Middle Ages

Map of northern Britain showing the Gododdin and other tribes c.600 AD

The Irish annals record that in 638, after the events related in Y Gododdin, "Etin" was besieged by the Angles under Oswald of Northumbria, and the Gododdin were defeated.[32] The territory around Edinburgh then became part of the Kingdom of Northumbria, which was itself absorbed by England in the 10th century. Lothian became part of Scotland, during the reign of Indulf (r.954–962).[33]

The archaeological evidence for the period in question is based entirely on the analysis of middens (domestic refuse heaps), with no evidence of structures. Few conclusions can therefore be derived about the status of the settlement during this period, although the midden deposits show no clear break since Roman times.[34]

St Margaret, depicted in a stained glass window in the chapel of Edinburgh Castle

High Middle Ages

The first documentary reference to a castle at Edinburgh is John of Fordun's account of the death of King Malcolm III. Fordun describes his widow, the future Saint Margaret, as residing at the "Castle of Maidens" when she is brought news of his death in November 1093. Fordun's account goes on to relate how Margaret died of grief within days, and how Malcolm's brother Donald Bane laid siege to the castle. However, Fordun's chronicle was not written until the later 14th century, and the near-contemporary account of the life of St Margaret by Bishop Turgot makes no mention of a castle.[35] During the reigns of Malcolm III and his sons, Edinburgh Castle became one of the most significant royal centres in Scotland.[36] Malcolm's son King Edgar died here in 1107.[37]Malcolm's youngest son, King David I (r.1124–1153), developed Edinburgh as a seat of royal power principally through his administrative reforms (termed by some modern scholars the Davidian Revolution).[38] Between 1139 and 1150, David held an assembly of nobles and churchmen, a precursor to the parliament of Scotland, at the castle.[36] Any buildings or defences would probably have been of timber,[39] although two stone buildings are documented as having existed in the 12th century. Of these, St. Margaret's Chapel remains at the summit of the rock. The second was a church, dedicated to St. Mary, which stood on the site of the Scottish National War Memorial.[39] Given that the southern part of the Upper Ward (where Crown Square is now sited) was not suited to being built upon until the construction of the vaults in the 15th century, it seems probable that any earlier buildings would have been located towards the northern part of the rock; that is around the area where St. Margaret's Chapel stands. This has led to a suggestion that the chapel is the last remnant of a square, stone keep, which would have formed the bulk of the 12th-century fortification.[40] The structure may have been similar to the keep of Carlisle Castle, which David I began after 1135.[41]

David's successor King Malcolm IV (r.1153–1165) reportedly stayed at Edinburgh more than at any other location.[37] But in 1174, King William "the Lion" (r.1165–1214) was captured by the English at the Battle of Alnwick. He was forced to sign the Treaty of Falaise to secure his release, in return for surrendering Edinburgh Castle, along with the castles of Berwick, Roxburgh and Stirling, to the English King, Henry II. The castle was occupied by the English for twelve years, until 1186, when it was returned to William as the dowry of his English bride, Ermengarde de Beaumont, who had been chosen for him by King Henry.[42] By the end of the 12th century, Edinburgh Castle was established as the main repository of Scotland's official state papers.[43]

Wars of Scottish Independence

Statues of Robert the Bruce by Thomas Clapperton and William Wallace by

Alexander Carrick were added to the Gatehouse entrance in 1929

In March 1296, Edward I launched an invasion of Scotland, unleashing the First War of Scottish Independence. Edinburgh Castle soon came under English control, surrendering after a three days long bombardment.[45] Following the siege, Edward had many of the Scottish legal records and royal treasures moved from the castle to England.[44] A large garrison numbering 325 men was installed in 1300.[46] Edward also brought to Scotland his master builders of the Welsh castles, including Thomas de Houghton and Master Walter of Hereford, both of whom travelled from Wales to Edinburgh.[47] After the death of Edward I in 1307, however, England's control over Scotland weakened. On 14 March 1314, a surprise night attack by Thomas Randolph, 1st Earl of Moray recaptured the castle. John Barbour's narrative poem The Brus relates how a party of thirty hand-picked men were guided by one William Francis, a member of the garrison who knew of a route along the north face of the Castle Rock and a place where the wall might be scaled. Making the difficult ascent, Randolph's men scaled the wall, surprised the garrison and took control.[48] Robert the Bruce immediately ordered the destruction of the castle's defences to prevent its re-occupation by the English.[49] Four months later, his army secured victory at the Battle of Bannockburn.[50]

After Bruce's death in 1329, Edward III of England determined to renew the attempted subjugation of Scotland and supported the claim of Edward Balliol, son of the former King John Balliol, over that of Bruce's young son David II. Edward invaded in 1333, marking the start of the Second War of Scottish Independence, and the English forces reoccupied and refortified Edinburgh Castle in 1335,[51] holding it until 1341. This time, the Scottish assault was led by William Douglas, Lord of Liddesdale. Douglas's party disguised themselves as merchants from Leith bringing supplies to the garrison. Driving a cart into the entrance, they halted it there to prevent the gates closing. A larger force hidden nearby rushed to join them and the castle was retaken.[42] The English garrison, numbering 100, were all killed.[51]

David's Tower and the 15th century

The 1357 Treaty of Berwick brought the Wars of Independence to a close. David II resumed his rule and set about rebuilding Edinburgh Castle which became his principal seat of government.[52] David's Tower was begun around 1367, and was incomplete when David died at the castle in 1371. It was completed by his successor, Robert II, in the 1370s. The tower stood on the site of the present Half Moon Battery and was connected by a section of curtain wall to the smaller Constable's Tower, a round tower built between 1375 and 1379 where the Portcullis Gate now stands.[42][53]

A late-16th-century depiction of the castle, from Braun & Hogenberg's Civitates orbis terrarum, showing David's Tower at the centre

In 1479, Alexander Stewart, Duke of Albany, was imprisoned in David's Tower for plotting against his brother, King James III (r.1460–1488). He escaped by getting his guards drunk, then lowering himself from a window on a rope.[55] Albany fled to France, then England, where he allied himself with King Edward IV. In 1482, Albany marched into Scotland with Richard, Duke of Gloucester (later King Richard III) and an English army. James III was trapped in the castle from 22 July to 29 September 1482 until he successfully negotiated a settlement.[55]

Edinburgh Castle as it may have looked before the Lang Siege of 1571-73,

with David's Tower and the Palace block, centre and left

Meanwhile, the royal family began to stay more frequently at the Abbey of Holyrood, about 1 mile (1.6 km) from the castle. Around the end of the fifteenth century, King James IV (r.1488–1513) built Holyroodhouse, by the abbey, as his principal Edinburgh residence, and the castle's role as a royal home subsequently declined.[55] James IV did, however, construct the Great Hall, which was completed in the early 16th century.[53]

16th century and the Lang Siege

Sir William Kirkcaldy of Grange, who held the castle on behalf of Queen Mary during the Lang Siege of 1571-73. Painting by Jean Clouet

The following year, the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, returned from France to begin her reign, which was marred by crises and quarrels amongst the powerful Protestant Scottish nobility. In 1565, the Queen made an unpopular marriage with Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, and the following year, in a small room of the Palace at Edinburgh Castle, she gave birth to their son James, who would later be King of both Scotland and England. Mary's reign was, however, brought to an abrupt end. Three months after the murder of Darnley at Kirk o' Field in 1567, she married James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, one of the chief murder suspects. A large proportion of the nobility rebelled, resulting ultimately in the imprisonment and forced abdication of Mary at Loch Leven Castle. She escaped and fled to England, but some of the nobility remained faithful to her cause. Edinburgh Castle was initially handed by its Captain, James Balfour, to the Regent Moray, who had forced Mary's abdication and now held power in the name of the infant King James VI. Shortly after the Battle of Langside, in May 1568, Moray appointed Sir William Kirkcaldy of Grange Keeper of the Castle.[55]

Detail from a contemporary drawing of Edinburgh Castle under siege in 1573, showing it surrounded by attacking batteries

The truce expired on 1 January 1573, and Grange began bombarding the town. His supplies of powder and shot, however, were running low, and despite having 40 cannon available, there were only seven gunners in the garrison.[70] The King's forces, now with the Earl of Morton in charge as regent, were making headway with plans for a siege. Trenches were dug to surround the castle, and St Margaret's Well was poisoned.[71] By February, all Queen Mary's other supporters had surrendered to the Regent, but Grange resolved to resist despite water shortages within the castle. The garrison continued to bombard the town, killing a number of citizens. They also made sorties to set fires, burning 100 houses in the town and then firing on anyone attempting to put out the flames.[72]

Sir William Drury, commander of Elizabeth I of England's Protestant

troops who brought the Lang Siege to an end in 1573. Unknown artist

Nova Scotia and Civil War

Much of the castle was subsequently rebuilt by Regent Morton, including the Spur, the new Half Moon Battery and the Portcullis Gate. Some of these works were supervised by William MacDowall, the master of work who fifteen years earlier had repaired David's Tower.[76] The Half Moon Battery, while impressive in size, is considered by historians to have been an ineffective and outdated artillery fortification.[77] This may have been due to a shortage of resources, although the battery's position obscuring the ancient David's Tower and enhancing the prominence of the palace block, has been seen as a significant decision.[78]The battered palace block remained unused, particularly after James VI departed to become King of England in 1603.[79] James had repairs carried out in 1584, and in 1615–1616 more extensive repairs were carried out in preparation for his return visit to Scotland.[80] The mason William Wallace and master of works James Murray introduced an early Scottish example of the double-pile block.[81] The principal external features were the three, three-storey oriel windows on the east façade, facing the town and emphasising that this was a palace rather than just a place of defence.[82] During his visit in 1617, James held court in the refurbished palace block, but still preferred to sleep at Holyrood.[53]

Memorial plaque to Sir William Alexander, on the Castle Esplanade

James' successor, King Charles I, visited Edinburgh Castle only once, hosting a feast in the Great Hall and staying the night before his Scottish coronation in 1633. This was the last occasion that a reigning monarch resided in the castle.[55] In 1639, in response to Charles' attempts to impose Episcopacy on the Scottish Church, civil war broke out between the King's forces and the Presbyterian Covenanters. The Covenanters, led by Alexander Leslie, captured Edinburgh Castle after a short siege, although it was restored to Charles after the Peace of Berwick in June the same year. The peace was short-lived, however, and the following year the Covenanters took the castle again, this time after a three-month siege, during which the garrison ran out of supplies. The Spur was badly damaged, and was demolished in the 1640s.[53] The Royalist commander James Graham, 1st Marquis of Montrose was imprisoned here after his capture in 1650.[84]

In May 1650, the Covenanters signed the Treaty of Breda, allying themselves with the exiled Charles II against the English Parliamentarians, who had executed his father the previous year. In response to the Scots proclaiming Charles King, Oliver Cromwell launched an invasion of Scotland, defeating the Covenanter army at Dunbar in September. Edinburgh Castle was taken after a three-month siege, which caused further damage. The Governor of the Castle, Colonel Walter Dundas, surrendered to Cromwell despite having enough supplies to hold out, allegedly from a desire to change sides.[84]

Garrison fortress: Jacobites and prisoners of war

An engraving of Edinburgh Castle made shortly before the creation of the Esplanade was begun in 1753

James VII was deposed and exiled by the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which installed William of Orange as King of England. Not long after, in early 1689, the Estates of Scotland, after convening to accept William formally as their new king, demanded that Duke of Gordon, Governor of the Castle, surrender the fortress. Gordon, who had been appointed by James VII as a fellow Catholic, refused. In March 1689, the castle was blockaded by 7,000 troops against a garrison of 160 men, further weakened by religious disputes. On 18 March, Viscount Dundee, intent on raising a rebellion in the Highlands, climbed up the western side of the Castle Rock to urge Gordon to hold the castle against the new King.[86] Gordon agreed, but during the ensuing siege he refused to fire upon the town, while the besiegers inflicted little damage on the castle. Despite Dundee's initial successes in the north, Gordon eventually surrendered on 14 June, due to dwindling supplies and having lost 70 men during the three-month siege.[87][88] Under the terms of the Acts of Union, which joined England and Scotland in 1707, Edinburgh was one of the four Scottish castles to be maintained and permanently garrisoned by the new British Army, the others being Stirling, Dumbarton and Blackness.[89]

Edinburgh Castle with the Nor Loch in foreground, around 1780, by Alexander Nasmyth

The last military action at the castle took place during the second Jacobite rising of 1745. The Jacobite army, under Charles Edward Stuart ("Bonnie Prince Charlie"), captured Edinburgh without a fight in September 1745, but the castle remained in the hands of its ageing Deputy Governor, General George Preston, who refused to surrender.[92] After their victory over the government army at Prestonpans on 21 September, the Jacobites attempted to blockade the castle. Preston's response was to bombard Jacobite positions within the town. After several buildings had been demolished and four people killed, Charles called off the blockade.[93][94] The Jacobites themselves had no heavy guns with which to respond, and by November they had marched into England, leaving Edinburgh to the castle garrison.[95]

Over the next century, the castle vaults were used to hold prisoners of war during several conflicts, including the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), the American War of Independence (1775–1783) and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815).[96] During this time, several new buildings were erected within the castle, including powder magazines, stores, the Governor's House (1742),[97] and the New Barracks (1796–1799).[98]

19th century to the present

King George IV waves from the battlements of the Half Moon Battery in 1822, drawn by James Skene

Soldiers of the castle garrison in an early photograph c.1845

Description

Edinburgh Castle is located at the top of the Royal Mile, at the west end of Edinburgh's Old Town. The volcanic Castle Rock offers a naturally defended position, with sheer cliffs to north and south, and a steep ascent from the west. The only easy approach is from the town to the east, and the castle's defences are situated accordingly, with a series of gates protecting the route to the summit of the Castle Rock.[109]

Plan of Edinburgh Castle

Key:

A Esplanade · B Gatehouse · C Ticket office · D Portcullis Gate & Argyle Tower · E Argyle Battery · F Mills Mount Battery & One o'Clock Gun · G Cartsheds · H Western Defences · I Hospital · J Butts Battery · K Scottish National War Museum · L Governors House · M New Barracks · N Military Prison · O Royal Scots Museum · P Foog's Gate · Q Reservoirs · R Mons Meg · S Pet Cemetery · T St. Margaret's Chapel · U Half Moon Battery · V Crown Square · W Royal Palace · X Great Hall · Y Queen Anne Building · Z Scottish National War Memorial

Key:

A Esplanade · B Gatehouse · C Ticket office · D Portcullis Gate & Argyle Tower · E Argyle Battery · F Mills Mount Battery & One o'Clock Gun · G Cartsheds · H Western Defences · I Hospital · J Butts Battery · K Scottish National War Museum · L Governors House · M New Barracks · N Military Prison · O Royal Scots Museum · P Foog's Gate · Q Reservoirs · R Mons Meg · S Pet Cemetery · T St. Margaret's Chapel · U Half Moon Battery · V Crown Square · W Royal Palace · X Great Hall · Y Queen Anne Building · Z Scottish National War Memorial

Outer defences

In front of the castle is a long sloping forecourt known as the Esplanade. Originally the Spur, a 16th-century hornwork, was located here. The present Esplanade was laid out as a parade ground in 1753, and extended in 1845.[53] It is upon this Esplanade that the Edinburgh Military Tattoo takes place annually. From the Esplanade the Half Moon Battery is prominent, with the Royal Palace to its left.[110]The Gatehouse at the head of the Esplanade was built as an architecturally cosmetic addition to the castle in 1888.[111] Statues of Robert the Bruce by Thomas Clapperton and William Wallace by Alexander Carrick were added in 1929, and the Latin motto Nemo me impune lacessit is inscribed above the gate. The dry ditch in front of the entrance was completed in its present form in 1742.[112] Within the Gatehouse are offices, and to the north is the most recent addition to the castle; the ticket office, completed in 2008 to a design by Gareth Hoskins Architects.[113] The road, built by James III in 1464 for the transport of cannon, leads upward and around to the north of the Half Moon Battery and the Forewall Battery, to the Portcullis Gate. In 1990, an alternative access was opened by digging a tunnel from the north of the esplanade to the north-west part of the castle, separating visitor traffic from service traffic.[114]

The Portcullis Gate

Portcullis Gate and Argyle Tower

The Portcullis Gate was begun by the Regent Morton after the Lang Siege of 1571–73 to replace the round Constable's Tower, which was destroyed in the siege.[115] In 1584 the upper parts of the Gatehouse were completed by William Schaw,[116] and these were further modified in 1750.[117] In 1886–1887 this plain building was replaced with a Scots Baronial tower, designed by the architect Hippolyte Blanc, although the original Portcullis Gate remains below. The new structure was named the Argyle Tower, from the fact that the 9th Earl of Argyll had been held here prior to his execution in 1685.[118] Described as "restoration in an extreme form",[118] the rebuilding of the Argyle Tower was the first in a series of works funded by the publisher William Nelson.[118]Just inside the gate is the Argyle Battery overlooking Princes Street, with Mills Mount Battery, the location of the One O'Clock Gun, to the west. Below these is the Low Defence, while at the base of the rock is the ruined Wellhouse Tower, built in 1362 to guard St. Margaret's Well.[119] This natural spring provided an important secondary source of water for the castle, the water being lifted up by a crane mounted on a platform known as the Crane Bastion.[120]

Military buildings

Governor's House (1742).

The New Barracks (1799).

National War Museum of Scotland

West of the Governor's House, a store for munitions was built in 1747–48 and later extended to form a courtyard, in which the main gunpowder magazine also stood.[126] In 1897 the area was remodelled as a military hospital, formerly housed in the Great Hall. The building to the south of this courtyard is now the National War Museum of Scotland, which forms part of the National Museums of Scotland. It was formerly known as the Scottish United Services Museum, and, prior to this, the Scottish Naval and Military Museum, when it was located in the Queen Anne Building.[127] It covers Scotland's military history over the past 400 years, and includes a wide range of military artefacts, such as uniforms, medals and weapons. The exhibits also illustrate the history and causes behind the many wars in which Scottish soldiers have been involved. Beside the museum is Butts Battery, named after the archery butts (targets) formerly placed here.[128] Below it are the Western Defences, where a postern, named the West Sally Port, gives access to the western slope of the rock.[129]Upper Ward

Foog's Gate

St. Margaret's Chapel

St. Margaret's Chapel

The oldest building in the castle, and in Edinburgh, is the small St. Margaret's Chapel.[4] One of the few 12th-century structures surviving in any Scottish castle,[41] it dates from the reign of King David I (r.1124–1153), who built it as a private chapel for the royal family and dedicated it to his mother, Saint Margaret of Scotland, who died in the castle in 1093. It survived the slighting of 1314, when the castle's defences were destroyed on the orders of Robert the Bruce, and was used as a gunpowder store from the 16th century, when the present roof was built. In 1845, it was "discovered" by the antiquary Daniel Wilson, while in use as part of the larger garrison chapel, and was restored in 1851–1852.[53] The chapel is still used for religious ceremonies, such as weddings.[131]Mons Meg

The siege gun Mons Meg described in a 17thC document as "the great iron murderer called Muckle-Meg" (muckle being Scots for 'big')

The 15th-century siege gun or bombard known as Mons Meg is displayed on a terrace in front of St. Margaret's Chapel. She was constructed in Flanders on the orders of Philip III, Duke of Burgundy in 1449, and given as a gift to King James II, the husband of his niece, in 1457.[56] The 13,000-pound (5.9 t) gun rests on a reconstructed carriage, the details of which were copied from an old stone relief that can be seen inside the tunnel of the Gatehouse at the castle entrance. Some of Meg's large gun stones, weighing around 330 pounds (150 kg) each,[132] are displayed alongside her. On 3 July 1558, she was fired in salute to celebrate the marriage of Mary, Queen of Scots to the French dauphin, François II. The royal Treasurer's Accounts of the time record a payment to soldiers for retrieving one of her stones from Wardie Muir near the River Forth, fully 2 miles (3 km) from the castle.[133] The gun has been defunct since her barrel burst while firing a salute to greet the Duke of Albany, the future King James VII and II, on his arrival in Edinburgh on 30 October 1681.[134]

Half Moon Battery and David's Tower

Half Moon Battery and Palace Block seen from the Esplanade

Artefacts found during excavation of David's Tower

Crown Square

The Royal Palace in Crown Square

Royal Palace

The Royal Palace comprises the former royal apartments, which were the residence of the later Stewart monarchs. It was begun in the mid 15th century, during the reign of James IV,[138] and it originally communicated with David's Tower.[112] The building was extensively remodelled for the visit of James VI to the castle in 1617, when state apartments for the King and Queen were built.[139] On the ground floor is the Laich (low) Hall, now called the King's Dining Room, and a small room, known as the Birth Chamber or Mary Room, where James VI was born to Mary, Queen of Scots, in June 1566. The commemorative painted ceiling and other decoration were added in 1617. On the first floor is the vaulted Crown Room, built in 1615 to house the Honours of Scotland: the crown, the sceptre and the sword of state.[140] The Stone of Scone, upon which the monarchs of Scotland were traditionally crowned, has been kept in the Crown Room since its return to Scotland in 1996. To the south of the palace is the Register House, built in the 1540s to accommodate state archives.[141]Great Hall

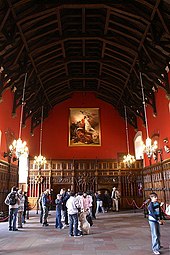

Interior of the Great Hall

Following Oliver Cromwell's seizure of the castle in 1650, the Great Hall was converted into a barracks for his troops; and in 1737 it was subdivided into three storeys to house 312 soldiers.[53] Following the construction of the New Barracks in the 1790s, it became a military hospital until 1897. It was then restored by Hippolyte Blanc in line with contemporary ideas of medieval architecture.[118] The Great Hall is still occasionally used for ceremonial occasions, and has been used as a venue on Hogmanay for BBC Scotland's Hogmanay Live programme. To the south of the hall is a section of curtain wall from the 14th century with a parapet of later date.[112]

The Queen Anne Building (centre-right)

Queen Anne Building

In the 16th century, this area housed the kitchens serving the adjacent Great Hall, and was later the site of the Royal Gunhouse.[145] The present building was named after Queen Anne and was built during the attempted Jacobite invasion by the Old Pretender in 1708. It was designed by Captain Theodore Dury, military engineer for Scotland, who also designed Dury's Battery, named in his honour, on the south side of the castle in 1713.[146] The Queen Anne Building provided accommodation for Staff Officers, but after the departure of the Army it was remodelled in the 1920s as the Naval and Military Museum, to complement the newly opened Scottish National War Memorial.[112] The museum later moved to the former hospital in the western part of the castle, and the building now houses a function suite and an education centre.[147]Scottish National War Memorial

The Scottish National War Memorial

The memorial commemorates Scottish soldiers, and those serving with Scottish regiments, who died in the two world wars and in more recent conflicts. Upon the altar within the Shrine, placed upon the highest point of the Castle Rock, is a sealed casket containing Rolls of Honour which list over 147,000 names of those soldiers killed in the First World War. After the Second World War, another 50,000 names were inscribed on Rolls of Honour held within the Hall, and further names continue to be added there.[149][151] The memorial is maintained by a charitable trust.[152]

Present use

Edinburgh Castle is in the ownership of the Scottish Ministers as heads of the devolved Scottish Government. The castle is run and administered, for the most part, by Historic Scotland, an executive agency of the Scottish Government, although the Army remains responsible for some areas, including the New Barracks block and the military museums. Both Historic Scotland and the Army share use of the Guardroom immediately inside the castle entrance.[153]

A re-enactor portraying James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, a husband of Mary, Queen of Scots, in the Great Hall

Tourist attraction

Historic Scotland undertakes the dual tasks of operating the castle as a commercially viable tourist attraction, while simultaneously bearing responsibility for conservation of the site. Edinburgh Castle remains the most popular paid visitor attraction in Scotland, with over 1.4 million visitors in 2013.[5][154] Historic Scotland maintains a number of facilities within the castle, including two cafés/restaurants, several shops, and numerous historical displays. An educational centre in the Queen Anne Building runs events for schools and educational groups, and employs re-enactors in costume and with period weaponry.[155]Military role

Sentries guarding the Gatehouse

Military tattoo

Royal Marines emerging from Edinburgh Castle during the military tattoo in 2005

One O'Clock Gun

The One O'Clock Gun being fired from Mill's Mount Battery

The original gun was an 18-pound muzzle-loading cannon, which needed four men to load, and was fired from the Half Moon Battery. This was replaced in 1913 by a 32-pound breech-loader, and in May 1952 by a 25-pound Howitzer.[160] The present One O'Clock Gun is an L118 Light Gun, brought into service on 30 November 2001.[161] On Sunday 2 April 1916, the One O'Clock Gun was fired in vain at a German Zeppelin during an air raid, the gun's only known use in war.[162]

The gun is now fired from Mill's Mount Battery, on the north face of the castle, by the District Gunner from the 105th Regiment Royal Artillery (Volunteers). Although the gun is no longer required for its original purpose, the ceremony has become a popular tourist attraction. The longest-serving District Gunner, Staff Sergeant Thomas McKay MBE, nicknamed "Tam the Gun", fired the One O'Clock Gun from 1979 until his retirement in January 2005. McKay helped establish the One O'Clock Gun Association, which opened a small exhibition at Mill's Mount, and published a book entitled What Time Does Edinburgh's One O'clock Gun Fire?.[163] In 2006 Sergeant Jamie Shannon, nicknamed "Shannon the Cannon", became the 29th District Gunner,[164] and in 2006 Bombardier Allison Jones became the first woman to fire the gun.[165]

Symbol of Edinburgh

The castle has become a recognisable symbol of Edinburgh, and of Scotland.[166] It appears, in stylised form, on the coats of arms of the City of Edinburgh and the University of Edinburgh. It also features on the badge of No. 603 (City of Edinburgh) Squadron which was based at RAF Turnhouse (now Edinburgh Airport) during Second World War.[167] Images of the castle are used as a logo by organisations including Edinburgh Rugby, the Edinburgh Evening News, Hibernian F.C. and the Edinburgh Marathon. It also appears on the "Castle series" of Royal Mail postage stamps, and has been represented on various issues of banknotes issued by Scottish clearing banks. In the 1960s the castle was illustrated on £5 notes issued by the National Commercial Bank of Scotland,[168] and since 1987 it has featured on the reverse of £1 notes issued by the Royal Bank of Scotland.[169] Since 2009 the castle, as part of Edinburgh's World Heritage Site, has appeared on £10 notes issued by the Clydesdale Bank.[170] The castle is a focal point for annual fireworks displays which mark Edinburgh's Hogmanay (new year) celebrations,[171] and the end of the Edinburgh Festival in the summer.[172]Geodesy

Up to 1891 Edinburgh Castle was the origin (meridian) of the 6 inch and 1:2500 Ordnance Survey maps of Edinburghshire. After that the Edinburghshire maps were drawn according to the meridian of The Buck in Aberdeenshire.

An Orchestra near the Heart of Midlothian 'Spitting Stone' on Royal Mile

Heart of Midlothian (Royal Mile)

The Heart of Midlothian

Together with brass markers bearing building dates, it records the position of the 15th-century Old Tolbooth, demolished in 1817, which was the administrative centre of the town, a prison, and one of several sites of public execution. The building features in Sir Walter Scott's novel The Heart of Midlothian, published in 1818.

The mosaic is named after the historic county of Midlothian of which Edinburgh is the county town. This is not to be confused with the council area of the same name which covers a smaller area and does not include the capital. The crest of the Edinburgh football team Heart of Midlothian is based upon this Heart.

Spitting

Visitors to Edinburgh will often notice people spitting on the Heart. A tolbooth (prison) stood on the site, where executions used to take place. The heart marks its doorway: the point of public execution.[2] Some people spit on the Heart. Although it now said to be done for good luck, it was originally done as a sign of disdain for the former prison. The spot lay directly outside the prison entrance, so the custom may have been begun by debtors on their release.References

- Monuments and Statues of Edinburgh, Michael T.R.B. Turnbull (Chambers) p.17

- A short documentary with both locals and tourists giving their differing views about the origin of spitting on The Heart.

- Picture of the Tolbooth in Edinburgh City Libraries' Capital Collections

Hollyrood Palace

Hollyrood Palace is at one end of the miracle mile and Edinburgh Castle is at the other end.

Hollyrood Palace

Wikipedia

The Palace of Holyroodhouse (/ˈhɒlɪˌruːd/ or /ˈhoʊlɪˌruːd/[1]), commonly referred to as Holyrood Palace, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland, Queen Elizabeth II. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinburgh Castle, Holyrood Palace has served as the principal residence of the Kings and Queens of Scots since the 16th century, and is a setting for state occasions and official entertaining.

Queen Elizabeth spends one week in residence at Holyrood Palace at the beginning of each summer, where she carries out a range of official engagements and ceremonies. The 16th century Historic Apartments of Mary, Queen of Scots and the State Apartments, used for official and state entertaining, are open to the public throughout the year, except when members of the Royal Family are in residence.

Architecture

The quadrangle designed by Sir William Bruce, drawn in the 1850s.[2]

The north and south fronts have symmetrical three-storey facades that rise behind to far left and right of 2-storey range with regular arrangement of bays. General repairs were completed by the architect Robert Reid between 1824–1834 that included the partial rebuilding of the south-west corner tower and refacing of the entire south front in ashlar to match that of the east.[3] The east front has 17 pilastered bays with superimposed columns at each floor. The ruins of the abbey church connect to the palace on the north-east corner. For the internal quadrangle, Bruce designed a colonaded piazza of nine arches on the north, south and east facades superimposed with columns from the three classical orders to indicate the importance of the three main floors. The plain Doric order is used for the services at ground floor, the Ionic order is used for the state apartments on the first floor, while the elaborate Corinthian order is used for the royal apartments on the second floor.[4]

Architectural historian Dan Cruickshank selected the palace as one of his eight choices for the 2002 BBC book The Story of Britain's Best Buildings.[5]

-

A 19th-century view of the Palace of Holyroodhouse from Calton Hill

Interior

The rooms open to the public include the 17th-century former King's apartments and Great Gallery, and the 16th-century apartments in the north-west tower.17th-century apartments

The landing of the Great Stair

Royal Dining Room

The Great Gallery, the largest room in the palace, links the King's Closet with the former Queen's apartments in the west range. The gallery is decorated with 110 portraits of the Scottish monarchs, beginning with the legendary Fergus I, who supposedly ruled from 330 BC. The portraits were all completed between 1684 and 1686 by Jacob de Wet II. This collection celebrated the royal bloodline of Scotland which the Scots upheld for its continuity and antiquity as an important part of their national identity in the seventeenth century.[10] After 1707, Scotland's representative peers were elected here to be sent to Westminster. Bonnie Prince Charlie held evening balls in the gallery during his brief occupation, and it later became a Catholic chapel for the Comte d'Artois. Today it is used for large functions including investitures and banquets.[11]

North-west tower

The suite of rooms on the first floor of the north-west tower comprises an audience chamber, accessed from a lobby next to the Great Gallery, and a bedroom, leading from which are two turret rooms or closets. These rooms were occupied by Lord Darnley in the 16th century, and later formed part of the Queen's apartment in the reconstructed palace, before being taken over by the Duke of Hamilton from 1684.[12] Queen Mary occupied an identical suite of rooms on the second floor of the tower: the bedchambers are linked by a private spiral stair. The Queen's outer chamber contains her oratory, and was the scene of the murder of David Rizzio, after he was dragged from the supper table in the northern turret room.[13] In later centuries, tourists were often convinced that they could see his blood stains on the floor.The wooden ceilings of both the main rooms date from Queen Mary's time, and the monograms MR (Maria Regina) and IR (Jacobus Rex) refer to her parents, Mary of Guise and James V. Shields commemorating Mary's marriage to Francis II of France are believed to have been carved in 1559 but put in their present position in 1617, when the grisaille frieze was also added.[14]

Gardens and grounds

Forecourt fountain

Statue of Edward VII outside the Palace

The buildings to the west of the palace, are the 19th-century guardhouse which replaced the tenements of a debtors' sanctuary, and adjacent to this, the former Holyrood Free Church and Duchess of Gordon's School, built in the 1840s. These buildings were converted into the Queen's Gallery in 2002 to display works of art from the Royal Collection.

There was formerly a Keeper of Holyrood Park, and the title was held on an hereditary basis by the Earls of Haddington. This was purchased by the Crown and the office extinguished in 1843 after disputes over the Keeper's right to allow quarrying within the Park.

"Big Royal Dig"

The Palace of Holyroodhouse, along with Buckingham Palace Garden and Windsor Castle, was excavated on 25–28 August 2006 as part of a special edition of Channel 4's archaeology series Time Team. The archaeologists uncovered part of the cloister of Holyrood Abbey, running in line with the existing abbey ruins, and a square tower associated with the 15th-century building works of James IV was discovered. The team failed to locate evidence of the real tennis court used by Queen Mary to the north of the palace, as the area had been built over in the 19th century. An area of reddened earth was discovered, which was linked with the Earl of Hertford's burning of Holyrood during the Rough Wooing of 1544. Among the objects found were a seal matrix used to stamp the wax seal on correspondence or documents,[19] and a French double tournois coin, minted by Gaston d'Orleans in 1634.[20]History

12th–15th centuries

The ruins of the Augustinian Holyrood Abbey

16th century

The gatehouse built by James IV, with the north-west tower of the palace behind, in a 1746 drawing by Thomas Sandby

Detail of a sketch made by an English soldier in 1544, showing the palace and abbey in front of Arthur's Seat.

The west range contained the King's lodgings and the entrance to the palace. James IV also oversaw construction of a two-storey gatehouse, fragments of which survive in the Abbey Courthouse. In 1512 a lion house was constructed to house the king's menagerie, which included a lion and a civet among other exotic beasts.[23] James V added to the palace between 1528 and 1536, beginning with the present north-west tower to provide new royal apartments. This was followed by reconstruction of the south and west ranges of the palace in the Renaissance style, with a new chapel in the south range. The former chapel in the north range was converted into the Council Chamber, where ceremonial events normally took place.[22] The west range contained the royal library and a suite of rooms, extending the royal apartments in the tower.[24] The symmetrical composition of the west façade suggested that a second tower at the south-west was planned, though this was never executed at the time.[25] Around a series of lesser courts were ranged the Governor's Tower, the armoury, the mint, a forge, kitchens and other service quarters.[25]

In 1544, during the War of the Rough Wooing, the Earl of Hertford sacked Edinburgh, and Holyrood was looted and burned. Repairs were made, but the altars were destroyed by a Reforming mob in 1559.[24] After the Scottish Reformation was formalised, the abbey buildings were neglected, and the choir and transepts of the abbey church were pulled down in 1570. The nave was retained as the parish church of the Canongate.[24]

The Murder of David Rizzio, painted in 1833 by William Allan.

During the subsequent Marian civil war, on 25 July 1571, William Kirkcaldy of Grange bombarded the Palace with cannon placed in the Black Friar Yard, near the Pleasance.[28] James VI took up residence at Holyrood in 1579 at the age of 13 years. His wife, Anne of Denmark, was crowned in the diminished abbey church in 1590, at which time the royal household at the palace numbered around 600 persons.[26]

17th century

The west range of the palace drawn around 1649 by James Gordon of Rothiemay, prior to reconstruction in the 1670s.

In 1650, either by accident or design, the east range of the palace was set on fire during its occupation by Oliver Cromwell's soldiers. After this, the eastern parts of the palace were effectively abandoned. The remaining parts were used as barracks, and a two-storey block was added to the west range in 1659.[citation needed]

The following year saw the Restoration of Charles II in England and Scotland. The Privy Council was reconstituted and once more met at Holyrood. Repairs were put in hand to allow use of the building by the Earl of Lauderdale, the Secretary of State for Scotland, and a full survey was carried out in 1663 by John Mylne.[30] In 1670, £30,000 was set aside by the Privy Council for the rebuilding of Holyrood.[31]

Plans for complete reconstruction were drawn up by Sir William Bruce, the Surveyor of the King's Works, and Robert Mylne, the King's Master Mason. The design included a south-west tower to mirror the existing tower, a plan which had existed since at least Charles I's time. Following criticism from Charles II, Bruce redesigned the interior layout to provide suites of royal apartments on the first floor: the Queen's apartment on the west side; and the King's apartment on the south and east sides. The two were linked by a gallery to the north, and a council chamber occupied the south-west tower.[31]

Work began in July 1671, starting at the north-west, which was ready for use by Lauderdale the following year. In 1675 Lord Hatton became the first of many nobles to take up a grace-and-favour apartment in the palace. The following year the decision was taken to rebuild the west range of the palace, and to construct a kitchen block to the south-east of the quadrangle. Bruce's appointment as architect of the project was cancelled in 1678, with the remaining work being overseen by Hatton.[31] By 1679 the palace had been re-constructed, largely in its present form. Craftsmen employed included the Dutch carpenters Alexander Eizat and Jan van Santvoort, and their countryman Jacob de Wet who painted several ceilings. The elaborate plasterwork was done by John Houlbert and George Dunsterfield.[32]

Interior work was still in progress when the James, Duke of Albany, the future James VII and II, and his wife Mary of Modena visited that year.[3] They returned to live at Holyrood between 1680 and 1682, in the aftermath of the Exclusion crisis, which had severely impacted James' popularity in England. When he acceded to the throne in 1685, the Catholic king set up a Jesuit college in the Chancellor's Lodging to the south of the palace. The abbey was adapted as a chapel for the Order of the Thistle in 1687–88. The architect was James Smith, and carvings were done by Grinling Gibbons and William Morgan. The interiors of this chapel, and the Jesuit college, were subsequently destroyed by an anti-Catholic mob, following the beginning of the Glorious Revolution in late 1688.[3] In 1691 the Kirk of the Canongate was completed, to replace the abbey as the local parish church, and it is at the Kirk of the Canongate that the Queen today attends services when in residence at Holyrood Palace.

18th century

A view of the palace and abbey in 1789

Bonnie Prince Charlie held court at Holyrood for five weeks in September and October 1745, during the Jacobite Rising. Charles occupied the Duke of Hamilton's apartments rather than the unkempt king's rooms, and held court in the Gallery. The following year, government troops were billeted in the palace after the Battle of Falkirk, when they damaged the royal portraits in the gallery, and the Duke of Cumberland stayed here on his way to Culloden.[34] Meanwhile, the neglect continued: the roof of the abbey church collapsed in 1768, leaving it as it currently stands. However, the potential of the palace as a tourist attraction was already being recognised, with the Duke of Hamilton allowing paying guests to view Queen Mary's apartments in the north-west tower.[35]

The precincts of Holyrood Abbey, extending to the whole of Holyrood Park, had been designated as a debtors' sanctuary since the 16th century. Those in debt could escape their creditors, and imprisonment, by taking up residence within the sanctuary, and a small community grew up to the west of the palace. The residents, known colloquially as "Abbey Lairds", were able to leave the sanctuary on Sundays, when no arrests were permitted. The area was controlled by a baillie, and by several constables, appointed by the Keeper of Holyroodhouse. The constables now form a ceremonial guard at the palace.[36]

19th century

Engraving of Holy Rood Palace by Thomas Hearne, drawn in 1778, engraving published 1800

King George IV became the first reigning monarch since Charles I to visit Holyrood, during his 1822 visit to Scotland. Although he stayed at Dalkeith Palace, the king held a levée (reception) at Holyrood, and was shown the historic apartments. He ordered repairs to the palace, but declared that Queen Mary's rooms should be protected from any future changes.[37] Over the next ten years, Robert Reid oversaw works including the demolition of all the buildings to the north and south of the main quadrangle.[3] In 1834 William IV agreed that the High Commissioner to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland could make use of the palace during the sitting of the assembly, and this tradition continues today.[3]

On the first visit of Queen Victoria to Scotland in 1842, she also stayed at Dalkeith, and was prevented from visiting Holyrood by an outbreak of Scarlet Fever.[38] In preparation for her 1850 visit, more renovations were carried out by Robert Matheson of the Office of Works, and the interiors were redecorated by David Ramsay Hay.[39] Over the next few years, the lodgings of the various nobles were gradually repossessed, and Victoria was able to take up a second floor apartment in 1871, freeing up the former royal apartments as dining and drawing rooms, as well as a throne room.[3] From 1854 the historic apartments in the north-west tower were formally opened to the public.[40]

20th century

Although Edward VII visited briefly in 1903, it was George V who transformed Holyrood into a 20th-century palace. Central heating and electric light were installed prior to his first visit in 1911, and after the First World War improvements to bathrooms and kitchens were carried out. In the 1920s the palace was formally designated as the monarch's official residence in Scotland, and became the location for regular royal ceremonies and events.[41]21st century

The Scottish version of the Royal Standard is flown when the monarch is in residence.